Ett osannolikt möte

Per-Ola Jansson

En klar oktoberdag 1999 är jag på väg till Lund för att fira min systers 60-årsdag. Väl ombord på tåget i Flemingsberg hamnar jag bredvid tre stadiga, silverhåriga och välklädda män. Den mitt emot har en slips som påminner om den som min far fått i gåva av en av min mors amerikanska kusiner. Slipsen i siden är bred, vinröd med inslag av vita och ljusröda blad. Efter en kort nick av mig yttrar sig slipsbäraren med ett vänligt ”welcome on board!” Amerikaner alltså!

Vi får upp konversation. Herrarna är på väg till emigrantmuseet i Växjö, släktforskare på jakt efter anfäder och anmödrar. Jag får reda på varifrån i USA de kommer, och vilka svenska rötter de känner till. Man är väl bekant med att dryga miljonen svenskar sökte sig till USA från mitten av 1800-talet till 1920-talet. Jag tar chansen och redogör för ”mina” emigranter. På min mors sida finns åtskilliga tremänningar till mig i Chicago. Kusiner till min mor lämnade Grängesberg och Silverhöjden och blev amerikaner. Min mormor återvände från Boston 1910 efter att ha varit husa i en svensk pastorsfamilj under några år. Hon färdades hem ombord på den hypermoderna Lusitania, som tyskarna sänkte 1915.

På min fars sida är det lite ”häftigare”, där finns en mytisk figur, en riktig superkändis. Här härstammar jag från svedjefinnar, som blandat sitt DNA med släktnamn som Bruse och Bång. Dessa rötter har växt samman i Grangärde Finnmark. Min farfars far är en ”finne” och modern en Bång. En kusin till min farfar, Gustaf Bång, föddes på finngården Laknäset intill sjön Närsen (Sormula) i Nås socken, en gård som blev något av en släktgård. Gustafs son Ture emigrerade till USA och blev där far till Rickard, men som i USA är mer känd som Richard Bong. I ett reportage i DalaDemokraten någon gång på 30-talet är några av syskonen Bong på hembesök i Nås iförda indianutstyrsel i imponerande fjäderskrud.

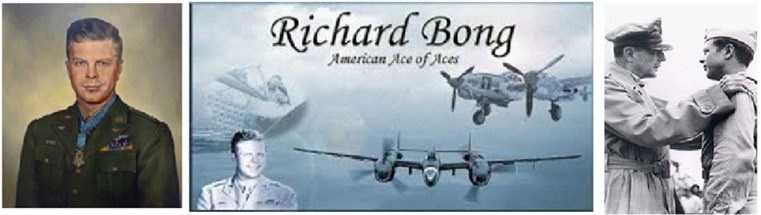

Här kan ni nu ta del av Richards meriter. På bilden till höger ser man Richard dekoreras av den amerikanske generalen Douglas MacArthur.

Richard Bong

Richard Ira Bong (September 24, 1920 – August 6, 1945), commonly called “Dick”, was a United States Army major who was a member of the Army Air Forces in World War II and a Medal of Honor recipient. He was one of the most decorated fighter pilots and the United States’ highest-scoring air ace in the war, having shot down at least 40 Japanese aircraft. All of his aerial victories were in the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter.

Early life

Bong, the son of Swedish immigrant parents, grew up on a farm in Poplar, Wisconsin, as one of nine children. He became interested in aircraft at an early age and was an avid model builder.

He began studying at Superior State Teachers College in 1938. While there, Bong enrolled in the Civilian Pilot Training Program and also took private flying lessons. On May 29, 1941, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps Aviation Cadet Program. One of his flight instructors was Captain Barry Goldwater (later Senator from Arizona).

Bong’s ability as a fighter pilot was recognized at training in northern California. He was commissioned a second lieutenant and awarded his pilot wings on January 19, 1942. His first assignment was as an instructor (gunnery) pilot at Luke Field, Arizona from January to May 1942. His first operational assignment was 0n May 6 to the 49th Fighter Squadron (FS), 14th Fighter Group at Hamilton Field, California, where he transitioned into the twin-engine P-38 Lightning.

On June 12, 1942, Bong flew very low (“buzzed”) over a house in nearby San Anselmo, the home of a pilot who had just been married. He was cited and temporarily grounded for breaking flying rules, along with three other P-38 pilots who had looped around the Golden Gate Bridge on the same day.[1] For looping the Golden Gate Bridge, flying at a low level down Market Street in San Francisco and for blowing the clothes off of an Oakland woman’s clothesline, Bong was reprimanded by General George C. Kenney, commanding officer of the Fourth Air Force, who told him, “If you didn’t want to fly down Market Street, I wouldn’t have you in my Air Force, but you are not to do it any more and I mean what I say.” Kenney later wrote: “We needed kids like this lad.”[2] In all subsequent accounts, Bong denied flying under the Golden Gate Bridge.[3] Nevertheless, Bong was still grounded when the rest of his group was sent without him to England in July 1942. Bong then transferred to another Hamilton Field unit, 84th Fighter Squadron of the 78th Fighter Group. From there Bong was sent to the Southwest Pacific Area.

On September 10, 1942, Lt. Bong was assigned to the 9th Fighter Squadron (aka “Flying Knights”), 49th Fighter Group, based at Darwin, Australia. While the squadron waited for delivery of the scarce Lockheed P-38s, Bong and other 9th FS pilots flew missions with the 39th FS, 35th Fighter Group, based in Port Moresby, New Guinea, to gain combat experience. On December 27, 1942, Bong claimed his initial aerial victory, shooting down a Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” and a Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar” over Buna (during the Battle of Buna-Gona). For this action Bong was awarded the Silver Star.

In March 1943, Bong returned to the 49th FG, now at Schwimmer Field near Port Moresby, New Guinea. In April, he was promoted to first lieutenant. [4] On July 26, 1943, Bong shot down four Japanese fighters over Lae, an accomplishment that earned him the Distinguished Service Cross. In August, he was promoted to captain. [5] While on leave to the United States in November and December 1943, Bong met Marge Vattendahl at a Superior State Teachers’ College Homecoming event and began dating her. After returning to the Southwest Pacific in January 1944, he named his P-38 “Marge” and adorned the nose with her photo.[6] By April 1944, Captain Bong had shot down 27 Japanese aircraft, surpassing Eddie Rickenbacker’s American record of 26 credited victories in World War I. In April, he was promoted to major.[7]

After another leave in the U.S. in May 1944, Major Bong returned to New Guinea in September. Though assigned to the V Fighter Command staff and not required to fly combat missions, Bong continued flying from Tacloban, Leyte, during the Philippines campaign, increasing his official air-to-air victory total to 40 by December.

Bong considered his gunnery accuracy to be poor, so he compensated by getting as close to his targets as possible to make sure he hit them. In some cases he flew through the debris of exploding enemy aircraft, and on one occasion actually collided with his target, which he claimed as a “probable” victory.

Medal of Honor

Upon the recommendation of Far East Air Force commander General George Kenney, Bong received the Medal of Honor from General Douglas MacArthur in a special ceremony in December 1944. Bong’s Medal of Honor citation states that he flew combat missions despite his status as an “instructor”, which was one of his duties as standardization officer for V Fighter Command. His rank of major would have qualified him for a squadron command, but he always flew as a flight (four-plane) or element (two-plane) leader.

In January 1945, General Kenney sent America’s ace of aces home for good. Bong married Marge and participated in numerous PR activities, such as promoting the sale of war bonds.

Death

Bong was killed in 1945 while testing a P-80A similar to this one. His death was featured prominently in national newspapers, even though it occurred on the same day as the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Bong then became a test pilot assigned to Lockheed’s Burbank, California, plant, where he flew P-80 Shooting Star jet fighters at the Lockheed Air Terminal. On August 6, 1945, the plane’s primary fuel pump malfunctioned during takeoff on the acceptance flight of P-80A 44-85048. Bong either forgot to switch to the auxiliary fuel pump, or for some reason was unable to do so.[8] Bong cleared away from the aircraft, but was too low for his parachute to deploy. The plane crashed into a narrow field at Oxnard St & Satsuma Ave, North Hollywood. His death was front-page news across the country, sharing space with the first news of the bombing of Hiroshima.[9]

At the time of the crash, Bong had accumulated four hours and fifteen minutes of flight time (totaling 12 flights) in the P-80. The I-16 fuel pump was a later addition to the plane (after an earlier fatal crash) and Bong himself was quoted by Captain Ray Crawford (another P-80 test/acceptance flight pilot who flew the day Bong was killed) as saying that he had forgotten to turn on the I-16 pump on an earlier flight.

In his autobiography, Chuck Yeager also writes, however, that part of the ingrained culture of test flying at the time, due to the fearsome mortality rates of the pilots, was anger directed at pilots who died in test flights, to avoid being overcome by sorrow for lost comrades. Bong’s brother Carl (who wrote his biography) questions the validity of reported circumstance that Bong repeated the same mistake so soon after mentioning it to another pilot. Carl’s book—Dear Mom, So We Have a War (1991)—contains numerous reports and findings from the crash investigations.

När jag närmade mig slutet på min “släktkrönika” chansade jag på att de amerikanska herrarna var bekanta med min släktings namn:

”One of my relatives was a famous pilot in World War two, Richard Bong, named Swede Bong!” Mannen mitt emot mig stelnade, fixerade mig tyst och sa´:

“I was his mechanic!”